Streaming is Broken IV: The Fortress: VPN and Gluetun

We have the server and our OS installed and configured. Before we start casting the actors who will play the lead roles, let’s pause for a moment to focus on the backstage. More precisely, on privacy. Regardless of whether you live in a country that actively punishes piracy or not, no one should know how you use your local network. Privacy matters!.

If you start a torrent download on the server right now, your real IP will be exposed to the world. Furthermore, ads, trackers, and telemetry data will flow freely through your network.

We have to put an end to this.

We aren’t just going to “install a VPN”; we are going to architect a secure network gateway that acts as a physical Kill Switch and segregates your network traffic to ensure speed where it matters and privacy where it is vital. Sounds complex, right? You’ll see that it’s not. You can bet on it.

The Sidecar Gateway Concept

The amateur approach is to install a VPN directly on the operating system (Host). This is bad because it encrypts everything (including your SSH access and local Jellyfin streaming), killing, butchering, and skinning performance.

Here, we will apply the Sidecar pattern:

We create a container (Gluetun) whose sole function is to open a secure VPN tunnel.

The “sensitive” containers (qBittorrent, Prowlarr, Arr-Stack) do not use the server’s network. They are configured with

network_mode: service:gluetun.They piggyback on Gluetun’s connection. They have no internet exit of their own.

The Hybrid Architecture: Dirty vs. Clean

As you may have noticed in the diagram above, and thinking about our CPU and system performance, we are going to opt for a crucial approach: Network Segregation. We will divide our network into two groups:

- The “Dirty” Group (VPN Tunnel):

Members: qBittorrent, Prowlarr, Sonarr, Radarr.

Reason: They download files, search public indexers, and need anonymity. I wouldn’t even say “need”—they must be anonymous at all costs.

Intercommunication: Since they share the same network “stack,” they talk to each other via localhost (e.g., Sonarr talks to qBit on localhost:8080).

- The “Clean” Group (Bridge/Host):

Members: Jellyfin, Kavita, AdGuard Home, Dashboard.

Reason: Jellyfin streams high-bitrate 4K video (80Mbps+) to your TV in the living room. If we passed this through the VPN, the encryption would consume useless CPU and add latency. This traffic must be local, fast, and direct.

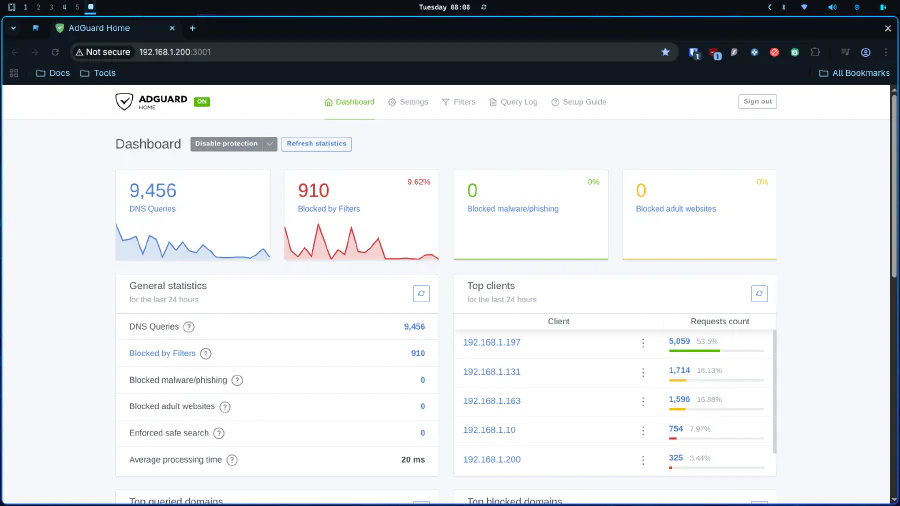

The DNS Guardian: AdGuard Home

No modern home server is complete without a traffic sanitation layer. Unlike that plugin you install in Chrome that only protects the browser, AdGuard Home operates at the network level. It is a “black hole” (DNS Sinkhole) for your entire house.

The logic is simple and brutal: when your TV Box, your iPad, or your PC tries to load a legitimate site, AdGuard lets it pass. But when these same devices try to connect to known advertising, tracking, telemetry, or malware servers, AdGuard returns a null address. It blocks the connection before the download of digital garbage even begins. The result? Clean browsing, bandwidth savings, and privacy even for devices where you can’t install blockers, like your Smart TV (which loves to spy on you).

Privacy matters!

The Port 53 Conflict: Surgery on Ubuntu

Here we encounter our first technical “Boss” of the installation. The DNS protocol operates, by default, on port 53. For AdGuard to function as the network’s main server, it needs to sit on this port. The problem is that modern Ubuntu Server is possessive. It comes with a service called systemd-resolved occupying port 53. If we tried to force the container up, Docker would scream an “Address already in use” error.

The amateur approach would be to try running AdGuard on an alternative port (like 5353), but that would break compatibility with most routers and devices. Our approach was surgical:

We didn’t kill the Ubuntu service (that would break the server’s own name resolution). We edited /etc/systemd/resolved.conf and disabled only the DNSStubListener.

Basically, we told Ubuntu: “Keep resolving names internally, but get off the public port 53 because AdGuard lives there now.” Turned out pretty damn cool, right?

As you saw in the architecture above, AdGuard resides in the Clean Group, outside the VPN tunnel. This is intentional and critical. DNS needs to be accessible by any device on your local network (LAN) with minimal latency. If we put AdGuard behind the VPN, every site request (“what is the IP for pornhub.com?”) would have to travel through the encrypted tunnel and back, making your browsing sluggish.

It sits on the bridge, light and fast, filtering the dirt at the entrance, while Gluetun protects the heavy traffic in the back.

Don’t forget change your router DHCP DNS param to homeserver’s IP.

We now have an armored network environment. Sensitive traffic is encapsulated in an unbreakable tunnel, media traffic flows freely on the local network, and the DNS is clean. The “Fortress” stands tall.

In the next post, I will explain the magic of Hardlinks, how to solve the user permissions nightmare, and understand why folder structure is the secret to making automation work.